In the AERA Field Lab Richard Redding teaches Mohamed Hussein (far left) and Mohamed Raouf the basics of archaeozoology as part of the AERA Advanced Field School. Photo by Mark Lehner.

Editor’s Note: As AERA continues its mission of education and outreach, we delight in sharing our staff’s knowledge with new generations of students and scholars. This is especially rewarding when we have the chance to delve more deeply into an area during an Advanced Field School session with students who have a passion for a particular topic. Here, two students of AERA’s archaeozoologist Dr. Richard Redding, Mohamed Hussein Ahmed and Mohamed Raouf Badran, share their experiences and impressions of their training during the Giza 2018 field and lab season. We feel that the best way to train students is a hands-on approach to our current research topics. Mohamed and Mohamed did just that, jumping right in on new material from that season’s excavations at the Kromer Dump Site.

Become an AERA member or make a donation to help us continue training the next generation of Egyptian archaeologists. Your contribution helps provide supplies, equipment, and staff salaries for our field school program.

by Mohamed Hussein Ahmed and Mohamed Raouf Badran

The 2018 AERA-ARCE Field School training was a dream come true. It is important that people know that becoming an animal bone specialist in Egypt is not an easy thing. To even find such training in a university in Egypt is difficult, if not impossible. Both of us had an urgent need for this specialist training right now, as we are both working on our theses, and animal bone is a key component of our topics.

We each had an interest in animal bone and the information we can receive from studying it before we came to the field school. We both knew of Dr. Redding through his writings or his lectures, but there was not a chance to have this one-on-one specialist training with him. During our research, we would send emails to Dr. Redding asking for copies of articles or books, advice, opinions, or other help that we needed in our work, but it was not enough. It was hard to read the articles and understand them because they were full of difficult Latin terms and scientific abbreviations, and we needed help just to understand the specialist language. We told Dr. Redding we would be eager to have in-depth training, and he worked to make it possible during this year’s excavation season.

Overview of Our Work

Mohamed Raouf draws fish vertebrae from Richard Redding’s reference collection. The inset shows the vertebrae.

Over six weeks of intensive training, Dr. Redding gave us all the support we needed—comprehensive explanations, articles to read, reports and references to use in writing, tools for our future work, and practical applications and demonstrations through magnificent research trips that helped us in understanding archaeozoology. He used different ways of teaching, like his great presentations with the white board, his unbelievable comparative collection in the lab, regular exercises to test our identifications, using manuals for mammals, birds, and fish, and training in equipment like scales and calipers.

He began with a general introduction about the mammals, birds, and fish of ancient Egypt. Then he focused on the most common of each category that we might find archaeologically in our future work. It was not easy for us at the beginning as we received a good deal of new Latin and English terminology in this course, but Dr. Redding did his best to deliver the information with his easy approach. By the end of the course we were on the same page, meaning that we succeeded in understanding these very difficult Latin words even if we did not know their Arabic meaning.

By the end of the first two weeks of training we were not only able to identify small fragments of bird and fish, but also which part of the body they came from. Dr. Redding’s vast comparative collection played an important role in identifying the fish. Ancient Egyptians caught many types of fish, and without the comparative collection we would face difficulty in identifying it. This is especially true with the very small fragments of bone recovered from the wet-sieve process, where the soil from excavation is washed through a series of fine sieves after it is rough-sifted on site. But, with practice, we were able to identify the more common fish without using the comparative materials, in particular those of catfish and Nile perch.

For mammals, we quickly set to work identifying the fragments of cattle, sheep-goat, and pig. With more training we moved to more advanced tasks, like identifying sheep from goat, determining male from female, and recognizing the fusion on some elements of the bones. One amazing thing is that we were able to differentiate between the milk teeth and the permanent teeth by studying the eruption process, and we learned how to differentiate between herbivores and carnivores by their teeth!

Within this intensive course we learned the name of each bone in the body; we were able to recognize if a bone fragment is from the right or left side of the body; and we learned the terminology to describe bone fragments and their condition in the appropriate ways. By the end of the course we were able to give our own interpretation about the faunal remains that we identified and recorded. We enjoyed every moment of this training.

Beyond the Basics

Preparing fish for the skeletonizing process—the first step in making their own comparative collections. Mohamed Hassan, AERA Lab Assistant and a fish expert, stands ready to advise.

We started our real work by identifying faunal remains from the BBHT area of the main site. We did our best, but unfortunately the bone fragments from this area are small, very fragmented pieces. By this time, Dr. Redding had begun to receive the bone from the new Kromer excavations. He was very excited at how complete and numerous these bones are. When we saw the Kromer bone, we were both thinking how great it would be to work on this material, so we asked, “Can we work with you, Dr. Redding, on the Kromer bone?” And he answered “Yes, of course!” We were very happy to work on such amazing and unique material, and started working right away with him to identify and record the faunal remains from the Kromer excavations.

Unfortunately, after four weeks Dr. Redding had to leave to return to the US. But the work continued as if he was still with us. Dr. Mark Lehner visited us almost every day, following and supporting us, and asking questions and taking photos. We were very happy that they relied on us to complete the work. We did it together through good cooperation. Together we succeeded in identifying, recording, and entering the information in the database. Together we wrote and sent our weekly reports to the other AERA staff, and we even began to write the final report of this season.

Field Trips

Outside of the lab, there were other activities that we also found very informative. The weekly site tours of the ongoing work at the Kromer, Lost City, and Khentkawes Town sites helped us have a better understanding of each area, which is important for our interpretations in the final faunal report. Many research trips were arranged for us. These were diverse and covered several aspects of archaeozoological work, including visits to the Giza Zoo and Zoological Museum, the Giza Fish Market, the tombs of Saqqara, and a scientific conference where Dr. Redding presented a paper on the material from the Heit el-Ghurab site.

A Trip to the Zoo

While we were learning mammals we took a trip to the Giza Zoo, where we had a good chance to see many of the animals we may find in the archaeological remains of Egyptian sites. We had a good overview from Dr. Redding on animals like lions, tigers, giraffes, monkeys, and birds.

The trip also included a short visit to the Zoological Museum—a great museum with many animal skeletons on display. It was a very interesting and important visit for us. We talked with the Zoological Museum’s manager about their collection and where and how they obtain the skeletons for the museum. Seeing such a large collection, we wondered if it would be possible for us to practice with and study this bone in the future. It would be a great opportunity for us to handle and identify these different animal bones, especially the animals that we might encounter archaeologically. In thinking about that, we approached the Ministry of Antiquities about having a joint understanding so that we might work with the Zoo and the Zoological Museum for future study. The Ministry agreed and we now have an approval letter for future cooperation. We made a good connection with the Zoo and museum staff, and found them very friendly and helpful.

Fish Week

At the Giza Fish Market, Mohamed Raouf (left), and Mohamed Hussein have a conversation with the head of the market about the price of fish and patterns of consumption.

Fish week was both wonderful and difficult because we received so much information about fish that we needed more time than the one week allowed. We discovered that “fish” are not only the five common types of fish that we consume in modern Egypt, but that it is a big tree or a whole community of fish that we did not know about before this field school. Dr. Redding explained to us the different types of fish, their families, species, and sex, and many other facts about the science of fish. Then we started to learn the most common species of fish that are found archaeologically and how to identify the bones recovered from the site using the AERA comparative collection.

Dr. Redding arranged a fantastic trip to the Giza Fish Market. There we saw different types of Nile fish that are commonly found in archaeological sites, and some marine fish as well. We were fortunate to be guided by Dr. Redding as he gave us information for each kind of fish in the market. At the end of our trip he selected various kinds of fish for us to start our own comparative collections.

We spent a half day in the fish market before returning to the AERA-Egypt Center to begin skeletonizing fish for our collections. We skeletonized our fish by removing as much of the meat as possible without damaging the bones, then sealing the remnants in a container with flesh-eating beetles that will finish the work on the more delicate pieces. Dr. Redding brought out knives, saying “Start now to remove the meat carefully, keep the bones as they are, and skeletonize your own fish comparative collection.” We did this work with our own hands, and enjoyed it very much. After we finished the cleaning process, we hung the fish in the garden of the villa for a couple of days while waiting for the beetles to come, and then we saved the fish in a closed box. This process might take three months or more, depending on how fast the beetles work.

The market trip and this skeletonization process that we made had given us a great help and is key to learning the anatomy of the fish skeletons and developing our skills for differentiating the most common species of fish we would find archaeologically.

Researching in Tombs

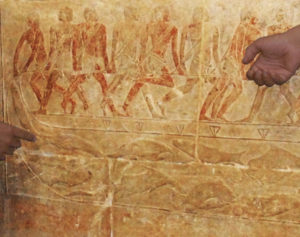

A scene of fishermen hauling their catch from the Tomb of Mereruka at Saqqara. The students were surprised that the depiction of the fish was so accurate they could identify them.

Dr. Redding also arranged an important field trip for us to visit Saqqara to see the tombs of Kagemni, Mereruka, and Ty. These three tombs are very rich in fish and fishing illustrations and show many of the same types of fish we had seen in the Giza Fish Market. Also there we examined the fish scenes and recognized the fish of the pharaohs from their representations.

We met Rasha Nasr, Archaeozoologist, and a student of Dr. Redding’s from the 2010 AERA-ARCE Field School. She offered us great help in visiting the tombs and also visiting the site of the excavations there, where they found a large amount of both human and animal bone, including dog mummies. Dr. Redding discussed with us how to deal with and study the dog mummies, including how to preserve them for the future.

Attending the “Food and Drink” IFAO Conference

Dr. Redding also supported our academic progress. He took us to a scientific conference titled “Food and Drink in Ancient Egypt and Sudan,” held at the Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale (IFAO) and the Polish Center of Mediterranean Archaeology in Cairo. There were great lectures based on the faunal and floral remains found at various sites. In addition to learning a great deal about ancient food and drink, we had opportunities at the conference to mix and mingle, form new relationships, and strengthen existing ones.

Filming

During this training we also participated in filming with Dr. Redding and Dr. Lehner. They encouraged us to speak on camera, and we both had an interview with an ARCE film crew to be shown in ARCE’s 2018 Annual Meeting in the US. We were happy to answer the questions of Dr. Louise Bertini, the Director of ARCE Egypt, about the field school training and how we benefitted from this course. Both Dr. Redding and Dr. Lehner encouraged us to speak in front of the camera, and this helped us to feel confident in doing so.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to our great teacher, Dr. Richard Redding, for his support, patience, and encouragement throughout this field school. It is not often that one finds a teacher who always finds the time for listening. We greatly appreciate all that he has done for us. He put us on the right track with a great amount of help, and trusted us with his own tools and comparative collection. Our thanks also go to Dr. Mark Lehner for closely following our training, providing many valuable comments, and sending helpful materials that improved our work. We are grateful for his support.

We would also like to show our gratitude to Dr. Bassem Gehad, Assistant to the Minister of Antiquities for Capacity Development and Human Resources. We also thank Dr. Mohamed Ragaey, the General Director of the zoos all over Egypt for his offer to study any skeletons in the museum, and Dr. Mervat, Director of the Zoological Museum of the Giza Zoo, for her hospitality and cooperation.

Mohamed Hussein Ahmed is working on the faunal remains from the Early Dynastic-period bone from the South Abydos excavations and is a student at South Valley University. He serves as the archaeozoologist for the South Abydos Excavation, Early Dynastic Cemetery and Settlement (SAEEDCS) Project, and after the conclusion of this year’s work was named the head of the archaeozoology department of the Scientific Center for Archaeological Field Training of Upper Egypt.

Mohamed Raouf Badran is a student at Mansoura University in the Department of Egyptology, where he is writing his thesis on nutrition in workmen’s communities in ancient Egypt. Following the training with Dr. Redding, he participated in another in-depth AERA-ARCE workshop on archaeological data management. He is currently an Inspector at the Giza Pyramids Inspectorate.

Become an AERA member or make a donation to help us continue training the next generation of Egyptian archaeologists. Your contribution helps provide supplies, equipment, and staff salaries for our field school program.