How Old Are the Pyramids?

Introduction

Archaeologists believe Egypt’s large pyramids are the work of the Old Kingdom society that rose to prominence in the Nile Valley after 3000 B.C. Historical analysis tells us that the Egyptians built the Giza Pyramids in a span of 85 years between 2589 and 2504 BC.

Interest in Egyptian chronology is widespread in both popular and scholarly circles. We wanted to use science to test the accepted historical dates of several Old Kingdom monuments.

One radioactive, or unstable, carbon isotope is C14, which decays over time and therefore provides scientists with a kind of clock for measuring the age of organic material.

The earliest experiments in radiocarbon dating were done on ancient material from Egypt. Willard F. Libby’s team obtained acacia wood from the 3rd Dynasty Step Pyramid of Djoser to test a hypothesis they had developed.

Libby reasoned that since the half-life of C14 was 5568 years, the Djoser sample’s C14 concentration should be about 50% of the concentration found in living wood (for further details, see Arnold and Libby, 1949). The results proved their hypothesis correct.

Subsequent work with radiocarbon testing raised questions about the fluctuation of atmospheric C14 over time. Scientists have developed calibration techniques to adjust for these fluctuations.

1984

In 1984 we conducted radiocarbon dating on material from Egyptian Old Kingdom monuments (financed by friends and supporters of the Edgar Cayce Foundation). We then compared our results with the mid-point dates of the kings to whom the monuments belonged (Cambridge Ancient History, 3rd ed.).

The average radiocarbon dates were 374 years earlier than expected.

In spite of this discrepancy, the radiocarbon dates confirmed that the Great Pyramid belonged to the historical era studied by Egyptologists.

1994-1995

In 1994-1995 the David H. Koch Foundation supported us for another round of radiocarbon dating.

We broadened our sampling to include material from:

- The 1st Dynasty tombs at Saqqara (2920-2770 BC).

- The Djoser pyramid (2630-2611 BC).

- The Giza Pyramids (2551-2472BC).

- A selection of 5th Dynasty pyramids (2465-2323 BC).

- A selection of 6th Dynasty pyramids (2323-2150 BC).

- A selection of Middle Kingdom pyramids (2040-1640 BC).

We also took samples from our Giza Plateau Mapping Project Lost City excavations (4th Dynasty), where we discovered two largely intact bakeries in 1991. Ancient baking left deposits of ash and charcoal, which are very useful for dating.

The 1995 set of radiocarbon dates tended to be 100 to 200 years older than the Cambridge Ancient History dates, which was about 200 years younger than our 1984 dates.

Comparison 1984/1995

The number of dates from the two projects was only large enough to allow for statistical comparisons for the pyramids of Djoser, Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure.

There are two striking results.

First, there are significant discrepancies between the 1984 and 1995 dates for Khufu and Khafre, but not for Djoser and Menkaure.

Second, the 1995 dates vary widely even for a single monument. For Khufu’s Great Pyramid, they scatter over a range of about 400 years.

Date agreements

We have fair agreement for the 1st Dynasty tombs at North Saqqara between our historical dates, previous radiocarbon dates, and our radiocarbon dates on reed material.

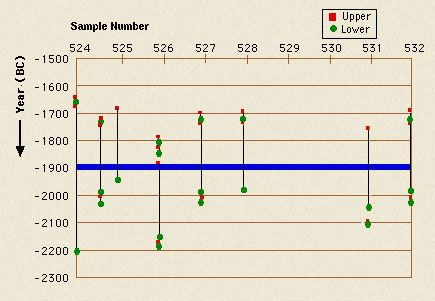

We also have fair agreement between our radiocarbon dates and historical dates for the Middle Kingdom. Eight calibrated dates on straw from the pyramid of Senwosret II (1897-1878 BC) ranged from 103 years older to 78 years younger than the historical dates for his reign.

Four of the Senwosret II dates were only off by 30, 24, 14, and three years. Significantly, the older date was on charcoal (see “old-wood problem” below).

Test results from Middle Kingdom pyramid (Senwosret II).

The old-wood problem

Ancient Egypt’s population was restricted to the narrow confines of the Nile Valley with, we assume, a sparse cover of trees. It is likely that, by the pyramid age, the Egyptians had been intensively exploiting wood for fuel for a long time.

Because of the scarcity and expense of wood, the Egyptians would reuse pieces of wood as much as possible. Some of this recycled wood was burned, for example, in mortar preparation. If a piece of wood was already centuries old when it was burned, radiocarbon dates of the resulting charcoal would be centuries older than the mortar for which it was burned.

We thought that it was unlikely that the pyramid builders consistently used centuries-old wood as fuel in preparing mortar. The 1984 results left us with too little data to conclude that the historical chronology of the Old Kingdom was wrong by nearly 400 years, but we considered this at least a possibility.

Alternatively, if our radiocarbon estimations were in error for some reason, we had to assume that many other dates obtained from Egyptian materials were also suspect. This prompted the second, larger, 1995 study.

Old Kingdom problem

If the Middle Kingdom radiocarbon dates are good, why are the Old Kingdom radiocarbon dates from pyramids so problematic?

The pyramid builders often reused old cultural material, possibly out of expedience or to make a conscious connection between their pharaoh and his predecessors.

Beneath the 3rd Dynasty pyramid of pharaoh Djoser, early explorers found more than 40,000 stone vessels. These vessels included inscriptions of most of the kings of the 1st and 2nd Dynasties, but Djoser’s name occurred only once. Did Djoser gather and reuse vases that were already 200 years old from tombs at North Saqqara?

In the 12th Dynasty, Amenemhet I (1991-1962 BC) left clear evidence of this kind of recycling. He took pieces of Old Kingdom tomb chapels and pyramid temples (including those of the Giza Pyramids) and dumped them into the core of his pyramid at Lisht.

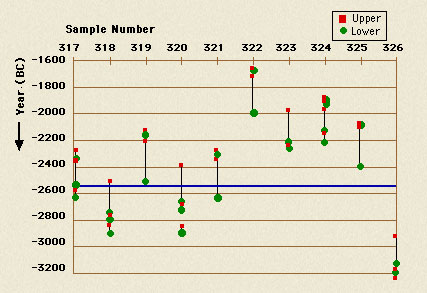

Test results from 5th Dynasty pyramid (Sahure)

Three of the eight radiocarbon dates from samples taken at our excavation at the Lost City are almost direct hits on Menkaure’s historical dates: 2532- 2504 BC. The other five range from 350 to 100 years older.

Our radiocarbon results from the Lost City site suggest that the dates on charcoal scatter widely, like those from the pyramids, with many dates older than the historical estimate. The inhabitants were very likely recycling their own settlement debris during the 85 or so years that they were building pyramids.

Conclusions

It may have been premature to dismiss the old wood problem in our 1984 study. Radiocarbon dating can only tell us when a tree died, not when it was last used. Wood may lay around for centuries before being burned, especially in a dry climate like Egypt.

Also, any living forest or stand of trees will have old trees and very young shoots. Any individual tree will have old parts (the inner rings) and very young parts (the outer rings and small branches).

Do our radiocarbon dates reflect the Old Kingdom deforestation of Egypt?

Did the pyramid builders exploit whatever wood they could harvest?

Or did they have to scavenge for wood to burn tons of gypsum for mortar, to forge copper chisels, and to bake bread for thousands of assembled laborers?

The giant stone pyramids in the early Old Kingdom may mark a major depletion of Egypt’s exploitable wood. This may be the reason for the wide scatter and history-unfriendly radiocarbon dating results from the Old Kingdom.

While the multiple old-wood effects make it difficult to obtain pinpoint age estimates of pyramids, the David H. Koch Pyramids Radiocarbon Project now has us thinking about forest ecologies, site formation processes, and ancient industry and its environmental impact—in sum, the society and economy that left the Egyptian pyramids as hallmarks for all later humanity.

See also: Bonani G, Haas H, Hawass Z, Lehner M, Nakhla S, Nolan J, Wenke R, Wölfli W. “Radiocarbon Dates of Old and Middle Kingdom Monuments in Egypt,” Radiocarbon 43, No. 3 (2001), 1297-1320(24).

What is radiocarbon dating?

All living things are built of carbon atoms. There are various isotopes, or species, of carbon atoms with the same atomic number but different mass.

One radioactive, or unstable, carbon isotope is C14, which decays over time and therefore provides scientists with a kind of clock for measuring the age of organic material.

While alive, all plants and animals take C14 into their bodies. The numbers of C14 atoms and non-radioactive carbon atoms remain approximately the same over time during the organism’s life. As soon as a plant or animal dies, the carbon uptake stops. The radioactive carbon isotope is no longer replenished; it only decays.

Scientists have calculated the rate at which C14 decays. By measuring how much C14 remains in a sample of organic material, we can estimate its age within a range of dates.

Samples older than 50,000 to 60,000 years are not useful for radiocarbon testing because by then, the amount of C14 remaining is too small to be dated. But material from the time of the pyramids lends itself well to radiocarbon dating because they fall into the 2575-1640 date range.

Radiocarbon technicians prefer to test wood and wood charcoal because their high molecular weight mitigates material loss during the rigorous pretreatments required for radiocarbon testing. We focused our collection efforts on tiny pieces of these materials, along with reed and straw left by the ancient builders.

The David H. Koch Pyramids Radiocarbon Project was a collaborative effort of Shawki Nakhla and Zahi Hawass, The Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities; Georges Bonani and Willy Wölfli, Institüt für Mittelenergiephysik, Eidgenossische Technische Hochschule; Herbert Haas, Desert Research Institute; Mark Lehner, The Oriental Institute and the Harvard Semitic Museum; Robert Wenke, University of Washington; John Nolan, University of Chicago; and Wilma Wetterstrom, Harvard Botanical Museum. The project was administered by Ancient Egypt Research Associates, Inc.